Oksefjell Ebeling, Signe and Jarle Ebeling. 2020. “Contrastive Analysis,

Tertium Comparationis and Corpora.” Nordic Journal of English Studies

19(1):97-117.

Contrastive Analysis, Tertium Comparationis and

Corpora

Signe Oksefjell Ebeling and Jarle Ebeling, University of Oslo

Abstract

This paper highlights the importance of a common ground, or tertium comparationis, in

order to establish unbiased cross-linguistic equivalence in contrastive studies. Following

an outline of the two main types of corpora used in contrastive analysis—comparable and

parallel bidirectional—a discussion of how they relate to different tertia comparationis is

presented. This is further illustrated in a case study where the same phenomenon is

investigated based on the two types of corpora. It is concluded that a bidirectional parallel

corpus, relying on both comparable monolingual and bidirectional translation data, may

yield more robust insights into cross-linguistic matters than either of the two on their

own.

Keywords: contrastive analysis; tertium comparationis; comparable corpora; parallel

corpora; English; Norwegian; for NPgen sake

1. Introduction

This paper addresses one of the main challenges within the field of

contrastive lingusitics, namely equivalence, through a direct comparison

of two types of tertia comparationis. It is generally agreed that in order

to establish equivalence across languages, a sound tertium comparationis

is needed, i.e. an objective background of sameness that ensures that we

compare like with like. Several tertia comparationis have been launched

over the years, including surface form, deep structure and translation, but

no consensus has been reached (see e.g. James 1980; Ebeling & Ebeling

2013a). That form, or surface structure, alone is a poor basis for

comparison if the aim is to study meaning and/or function is

acknowledged by Biber (1995) in a contrastive study of relative

constructions, where he notes that “despite the obvious structural

similarities between relative constructions in Somali and English, the

distribution of these features indicates that they are serving very different

functions in the two languages” (Biber 1995: 75).

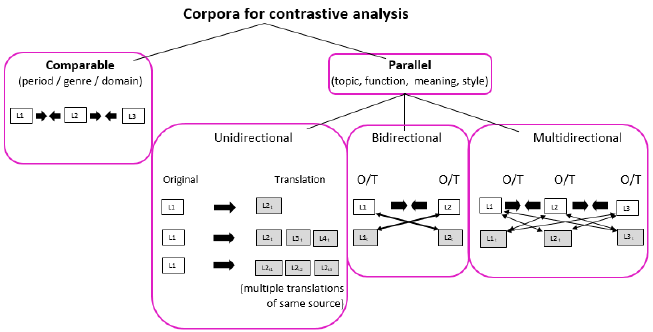

Within corpus-based contrastive analysis, the types of available

tertia comparationis are very much tied to the different types of corpora

Signe Oksefjell Ebeling and Jarle Ebeling

98

that are typically used in cross-linguistic research, i.e. comparable

corpora and parallel corpora of different kinds (e.g. uni-, bi- or

multidirectional). Johansson (2011) strongly believes in the advantages

of using parallel as opposed to comparable corpora:

The special advantage of parallel corpora is that they contain texts which are

intended to express the same meanings and have the same discourse functions in the

relevant languages. Using the source or the target language as a starting-point, we

can establish paradigms of correspondences. […] The most difficult problem in

using comparable corpora is knowing what to compare, i.e. relating forms which

have similar meanings and pragmatic functions. (Johansson 2011:126–127)

Arguments against using translations as the (only) tertium comparationis

in cross-linguistic studies come, in particular, from scholars who see

translations as a ‘third code’ (Frawley 1984), and who claim that

translations will deviate from the source text to a considerebale degree,

making them unsuitable as an empirical basis. Teubert (1996), for

instance, says that “[t]ranslations, however good and near-perfect they

may be (but rarely are) cannot but give a distorted picture of the

language they present” (1996: 247).

Against this backdrop, we will conduct the same study based on the

two types of corpora (comparable and parallel) representing different

tertia comparationis. To our knowledge no study has hitherto

systematically carried out the same study on the basis of comparable vs.

bidirectional parallel corpora and juxtaposed the analysis in the way done

here. We hope to be able to demonstrate the impact the type of corpus

might have regarding insights gained about cross-linguistic equivalence.

We start with a brief outline of modern contrastive analysis (CA) as

a systematic research paradigm in Section 2. Section 3 discusses

different kinds of contrastive corpora, how they relate to different tertia

comparationis and thus may have an impact on how equivalence in CA

is tackled. Also in Section 3, an overview of the pros and cons of such

“contrastive” corpora is presented. Section 4 introduces the English-

Norwegian contrastive case study that is used as a testbed for carrying

out the same study on the basis of a comparable vs. a bidirectional

parallel corpus, demonstrating two different tertia comparationis: similar

forms and translation (Sections 5 and 6, respectively). Some concluding

remarks are offered in Section 7.

Contrastive Analysis, Tertium Comparationis, Corpora

99

2. Modern Contrastive Analysis

In this section, we offer a brief discussion of a select few approaches

within modern contrastive analysis (CA). It would be impossible to

describe and discuss the many ways in which to conduct a CA that have

been proposed over the past 60 years or so in this short article. We refer

the interested reader to some important works, and references therein, for

more comprehensive and detailed accounts: Aijmer et al. (1996),

Altenberg & Granger (2002), Johansson (2007), Hasselgård (2010),

Ebeling & Ebeling (2013a) and Mair (2018) and articles published in the

journal Languages in Contrast (John Benjamins).

A much-used approach in CA is to take a perceived similarity, or

dissimilarity, between the languages to be compared as the point of

departure, be it at the level of lexis, syntax or semantics (meaning).

Based on the perceived similarity a null hypothesis, e.g. that the

items/phenomena to be compared are equivalent, can be formed and

tested. Chesterman (1998) advocates such an approach and recommends

the following steps, where the starting point, and first step, is a

(dis)similarity of any kind between phenomenon X in language A and

phenomenon Y in language B. A phenomenon can in principle be almost

anything: a situation, a gesture, a construction, a category or an item.

Based on the similarity, the following question is posed (step 2): what is

the nature of the similarity (form, meaning, function)? The third step

involves the description of the relationship between X and Y in the

compared languages, or as is more often the case, the relationship

between X in language A and Y1, Y2, Y3, etc. in language B (see e.g.

Dyvik (1998) and his semantic mirrors). Based on the outcome of step 3,

the null hypothesis can be corroborated or rejected. The resulting

description can also be used to enrich our knowledge of the individual

languages and/or the relationship between the languages compared, at

e.g. the formal, semantic and/or functional levels.

In addition to the rigorous method suggested by Chesterman, there

are other, more exploratory ways into a contrastive study. One fruitful

point of departure is any observed quantitative difference between

original and translated texts of the same type and size (e.g. Johansson

2007: Ch. 4). Yet another approach is to register zero correspondences in

a parallel corpus (e.g. Ebeling & Ebeling 2013b), that is where an item in

one language does not seem to have a (direct) correspondence in the

other language, and ask what the reasons for these non-correspondences

Signe Oksefjell Ebeling and Jarle Ebeling

100

may be. One could also start more opportunistically by choosing a word,

frame, pattern or construction in language A and record and analyse all

the corresponding items/units in language B, i.e. create a list of

translation paradigms, to describe similarities and differences at the

levels of, for instance, syntax and/or semantics (e.g. Johansson 2001 on

seem and its Norwegian correspondences). In all of these cases, close,

qualitative scrutiny of the differences should be part of the study. Note

that several of the more exploratory approaches require access to a

corpus of original texts and aligned translations.

To end this short description of ways of doing CA, we quote

Johansson (2012: 46) and what he calls “contrastive linguistics in a new

key”, i.e. contrastive analysis in which

• the focus on immediate applications is toned down;

• the contrastive study is text-based rather than a comparison

of systems in the abstract;

• the study draws on electronic corpora and the use of

computational tools.

The list sets modern CA apart from early (pre-corpora) CA where the

focus was on applied aims and applications, e.g. error analysis of

learners’ mistakes and on (intuitive) claims about differences between

languages or simply by comparing language systems, as found in e.g.

monolingual grammar books (see James 1980; Mair 2018).

By modern corpus-based contrastive analysis we understand research

which is grounded in empirical (corpus) data in two or more languages,

with the challenges and limitations that this entails, for instance with

regard to the type and amount of data available. This is in fact one of the

main challenges of modern contrastive research. We now turn to these

challenges in a comparison of comparable and parallel corpora.

3. Types of Corpora Used in Contrastive Analysis

There is a clear difference between comparable and parallel corpora. The

former are usually matched by period, genre and/or domain to enable the

contrastive analysis, while the latter consist of original and translated

texts in two or more languages, and are, in this way, also matched by

Contrastive Analysis, Tertium Comparationis, Corpora

101

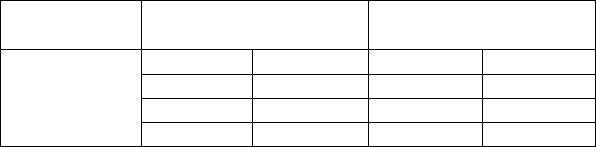

topic, function, meaning and style. Figure 1 presents an overview of

these two main types of corpora.

Figure 1. Corpora used in CA (inspired by Aijmer 2008; Johansson 2007; McEnery &

Xiao 2007)

As shown in Figure 1, in a comparable corpus, original texts in two or

more languages—L1, L2, L3 etc.—can be compared to each other,

pairwise (L1 vs. L2; L1 vs. L3; L2 vs. L3) or one can compare L1 vs. L2

& L3, L2 vs. L1 & L3, etc.

When it comes to parallel corpora, these can be further sub-divided

into unidirectional, bidirectional and multidirectional with an increasing

complexity of correspondences: from the simplest unidirectional corpus

between two languages (from Language 1 → Language 2

T

) to the most

complex multidirectional one between several languages, e.g. L1, L2 and

L3 with translations into the other languages (L1 → L2

T

; L1 → L3

T

; L2

→ L1

T

; L2 → L1

T

; L3 → L1

T

; L3 → L2

T

). In addition, the structure of

bidirectional and multilingual corpora enables comparisons of the

comparable type as well as comparisons of features of translation within

and across languages.

Corpus-based contrastive research between English and Norwegian

and between English and Swedish has often been conducted on the basis

Signe Oksefjell Ebeling and Jarle Ebeling

102

of a balanced, bidirectional, parallel corpus,

1

since, in addition to being

comparable, such a corpus gives the researchers the possibility of starting

the analysis in either language and in either original or translated texts

and, more importantly, to control for translation effects and source

language shining through (Johansson 2007; Teich 2003).

2

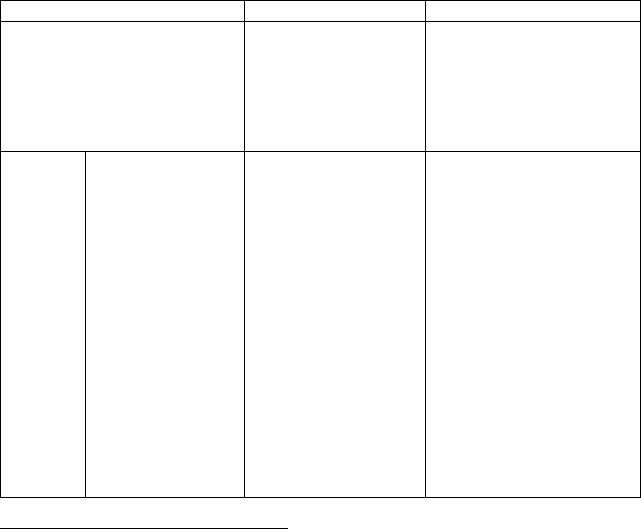

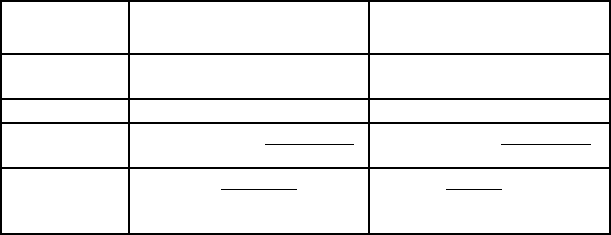

Before we present the case study, it is useful to keep the pros and

cons of the main types of contrastive corpora in mind. These are outlined

in Table 1, which is inspired by Altenberg & Granger (2002), Johansson

(2007), Aijmer (2008), Ebeling & Ebeling (2013a), and an adapted

version of Hasselgård (Forthc.)

Table 1. The pros and cons of corpus types for CA

Pros

Cons

Comparable corpora

• Not restricted to

translated text types

• More readily

available

• Comparison of

original language

• Criteria for

comparability (TC)?

• No alignment possible

• Cannot reveal sets of

cross-linguistic

correspondences

Parallel

corpora

Unidirectional

translation corpora

• Alignment is

possible

• Meaning and

function constant

across the

languages (a

relatively sound

TC is present)

• Possible to discover

(sets of) cross-

linguistic

correspondences

(‘translation

paradigms’)

• Restricted range of text

types

• Translation effects:

o Traces of source

language in translated

texts

o Traces of the

translation process,

including errors

1

See e.g. the bibliography of publications based on the English-Norwegian

Parallel Corpus and the English-Swedish Parallel Corpus:

https://www.hf.uio.no/ilos/tjenester/kunnskap/sprak/omc/enpc_espc_publication

s_2014.pdf

2

Translation effect has also been termed ‘translationese’ See e.g. Gellerstam

(1986) and Volansky et al. (2013).

Contrastive Analysis, Tertium Comparationis, Corpora

103

Balanced, bi-

/multidirectional

translation corpora

• Same as

unidirectional

translation copora

PLUS:

o Possible to check

translations in

both directions

(control for

translation

effects)

o Comparison of

original language

o A sounder TC is

present

• Even more restricted

range of text types

• Achieving balance of

text types between

directions of translations

Comparable corpora have one huge advantage over parallel corpora, and

that is that they are not restricted to text types that are translated. It is, for

instance, nearly impossible to find English translations of scientific texts

originally written in a Scandinavian language, since researchers and

scientists in the Scandinavian countries generally write in English.

One of the main challenges with comparable corpora is that the texts

in the different languages are not directly and explicitly linked to each

other linguistically. This means that it is hard to establish a sound and

objective tertium comparationis, since one cannot be absolutely sure that

one compares like with like. Even though the types of texts in the

languages compared represent a common ground suitable for

comparison, the actual items compared may not have been selected on

the basis of a tertium comparationis that fulfills all levels of linguistic

comparability: form, function and meaning. To some extent one may

compensate for this by using one’s bilingual knowledge or a dictionary.

Parallel corpora have the advantage that they can be aligned at

sentence level, thus making it relatively easy to recognise corresponding

items in original and translation, that is, a sound common ground on

which to build a direct comparison is present. This common ground has

been claimed to become even firmer and more objective if you have a bi-

or multidirectional parallel corpus, which is also in effect a comparable

corpus in that it contains original language data in all the languages

compared (cf. Johansson & Hofland 1994; Johansson 2007; Aijmer

2008).

We now turn to the case study where we will perform an analysis of

the same phenomenon in the two different types of corpora.

Signe Oksefjell Ebeling and Jarle Ebeling

104

4. Case Study: Background

The case study takes a previous contrastive investigation as its starting

point. Ebeling & Ebeling (2014) present a corpus-based contrastive

analysis of two similar-looking patterns in English and Norwegian,

namely for * sake and for * skyld, where the asterisk stands for a genitive

noun.

3

The present study is in many ways an experiment in the sense that an

attempt will be made to carve up the original study in a different way.

The purpose of the experiment is to demonstrate and put focus on the

pros and cons of two different tertia comparationis (TC) in contrastive

analysis. The first TC is based on sameness of form and draws on corpus

data from a comparable corpus of English and Norwegian, while the

second is based on (sameness of form and) translation data from a

bidirectional parallel corpus of English and Norwegian. The former will

be referred to as “the comparable study” (Section 5) and the latter as “the

bidirectional parallel study” (Section 6).

The corpus used for the occasion is the English-Norwegian Parallel

Corpus+ (ENPC+) (Ebeling & Ebeling 2013a), which is structured

according to Johansson’s parallel corpus model; thus it contains both

comparable and bidirectional translation data in one (Johansson &

Hofland 1994). The ENPC+ is an extended version of the fiction part of

the English-Norwegian Parallel Corpus (ibid.) and contains around 1.3

million running words of contemporary English and Norwegian fiction

texts and their respective translations into the other language.

4

In other

words, it is a balanced corpus amounting to rougly 5.2 million words in

total.

The comparable version of the study is based on material drawn from

the texts originally written in English and Norwegian only, while

material from both originals and translations will be explored in the

bidirectional parallel study.

3

There are exceptions to this in Norwegian, where no genitive marking of the

noun is found, e.g. for moro skyld (ʻfor fun sakeʼ). Moreover, the Oxford

English Dictionary notes that “[t]he omission of the ʼs is now obsolete, but it is

still not uncommon to write for conscience sake, for goodness sake, for

righteousness sake, etcˮ. However, no such instances were attested in our

material.

4

These include extracts of 10,000-15,000 words from 30 texts and nine full-text

novels.

Contrastive Analysis, Tertium Comparationis, Corpora

105

4.1 Preliminary Observations of the Patterns

Ebeling & Ebeling (2014: 192) start by outlining the meanings of the for

* sake pattern according to Oxford Dictionaries Online (now

Lexico.com): (a) for the purpose of, (b) out of consideration for or in

order to help or please someone, and (c) to express impatience,

annoyance, urgency, or desperation. It is argued that the Norwegian

pattern incorporates the same meanings, as attested in examples (1)–(3)

from Norwegian original texts with their translations into English.

(a) For the purpose of something

(1) For sikkerhets skyld ber jeg ham tie om at vi har en kopi.

(ToEg1N)

5

For safetyʼs sake, I ask him not to tell anyone that we have a copy.

(ToEg1TE)

(b) Out of consideration for or in order to help or please someone

(2) En gang sa hun at hun gjorde det for pappas skyld og for oss, så vi

hadde penger nok. (PeRy1N)

Once she said that she was doing it for Dadʼs sake, so that we

would have enough money. (PeRy1TE)

(c) To express impatience, annoyance, urgency, or desperation

(expletive use)

(3) Si noe, for Guds skyld! (LSC2)

6

Say something, for Godʼs sake! (LSC2T)

The examples serve to illustrate that, based on dictionary definitions,

bilingual competence and examples from translations, there is indeed a

perceived similarity between the two patterns, not only in terms of form,

but also in terms of meaning.

5

The corpus text code identifies the author of the text (ToEg = Tom Egeland),

text number by that author (1) and language (N). The code of the English

translation of this text is ToEg1TE. See Ebeling & Ebeling (2013a) for an

overview of texts and text codes included in the ENPC+.

6

In texts from the original ENPC, language is not specified in the corpus text

code, thus LSC2 (and not LSC2N).

Signe Oksefjell Ebeling and Jarle Ebeling

106

5. Comparable Version of the Study

We start by investigating the patterns on the basis of the comparable part

of the ENPC+, i.e. the use of for * sake in English originals vs. for *

skyld in the Norwegian originals. Following an analysis of the respective

concordance lines in these texts, our first observation is that all three

uses/meanings are attested in the original texts in both languages, e.g.

examples (4)–(9).

(a) For the purpose of something

(4) We stayed together for appearances’ sake, … (PeRo2E)

(5) … det videre søket etter Leike ville bare være for syns skyld.

(JoNe2N)

(b) Out of consideration for or in order to help or please someone

(6) Just for a while, then, another chapter or two — for Miriam’s sake.

(PaAu1E)

(7) … men for Mathias’ skyld, herregud, de hadde jo et barn sammen!

(JoNe1N)

(c) To express impatience, annoyance, urgency, or desperation

(expletive use)

(8) For God’s sake, stop! (MiWa1E)

(9) — Pass opp, for Guds skyld, ropte vi. (PePe1N)

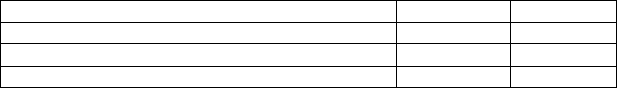

When each instance of the patterns is classified according to meaning,

striking cross-linguistic differences become apparent. As shown in Table

2, the preferred use is very different in the two languages: expletive is by

far the most common use in English and the purpose use is the most

common use in Norwegian.

Table 2. Distribution in the original texts according to meaning (Ebeling

& Ebeling 2014: 201)

Meaning

for * sake

EO

for * skyld

NO

Purpose

3

3.5%

47

73.4%

Consideration

17

20.0%

12

18.8%

Expletive

65

76.5%

5

7.8%

Total

85

64

Contrastive Analysis, Tertium Comparationis, Corpora

107

The difference can be summed up as follows, in terms of preferred use in

the two languages:

• English: Expletive>Consideration>Purpose

• Norwegian: Purpose>Consideration>Expletive

An almost symmetrically opposite use is thus noted for expletive and

purpose for * sake and for * skyld, with the consideration use nicely

placed in the middle and used with proportionally very similar

frequencies in the two languages (20% vs. 18.8%).

Further cross-linguistic (comparable) analysis reveals additional

differences in the use of the English and Norwegian patterns. These can

be summarized according to Sinclairʼs (1996, 1998) extended-units-of-

meaning (EUofM) model, in which the English and Norwegian patterns

can be said to operate as cores of two different EUofM. To elaborate: the

immediate context of the English and Norwegian patterns (cores),

studied through concordance lines, clearly show that, although they both

colligate with a noun in the genitive, they typically take different

collocations, have a different semantic preference, and ultimately a

different semantic prosody. The semantic prosody of the unit with the

English core for * sake is to express annoyance, bordering on the

negative, while Norwegian for * skyld is part of a more neutral unit

expressing purpose.

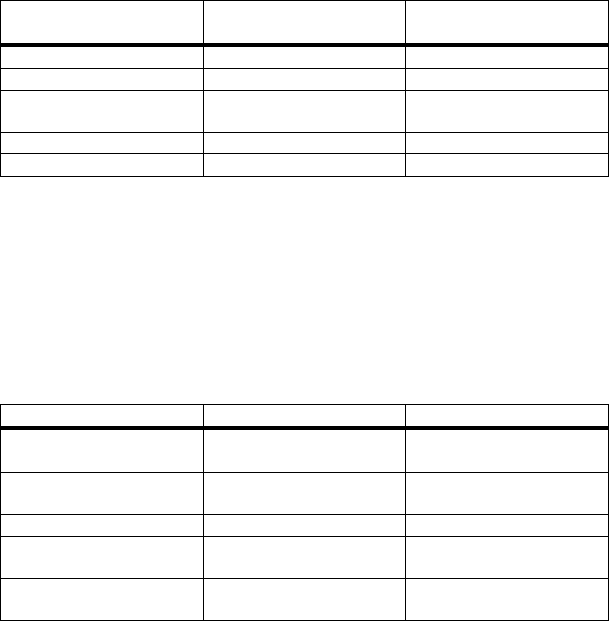

In the light of this analsyis, we can conlude that a comparable study

of the two patterns offers valuable cross-linguistic insights along the

lines outlined in Figure 2.

English

(Core: for * sake)

Norwegian

(Core: for * skyld)

Collocation

for [God’s / Christ’s / fuck’s]

sake

for [sikkerhets / syns / ordens]

skyld

Colligation

for NPgen sake

for NPgen skyld

Semantic

preference

words to do with religion, sex

words to do with arrangement

(order, safety, simplicity)

Semantic

prosody

(Negative) annoyance (in the

form of swearing or near-

swearing)

(Neutral) purpose (typically for

the purpose of safety)

Figure 2. for * sake and for * skyld as cores of different EUofM

Signe Oksefjell Ebeling and Jarle Ebeling

108

The comparable analysis raises a set of pertinent questions: how similar

are these two patterns? Have we compared like with like? And to make

sure we do that, how can we best capture expressions that are similar in

meaning to the for * sake or for *skyld patterns in the other language?

For example: How is the expletive use typically expressed in Norwegian

if not by the formally similar pattern?

To investigate this, we turn to the bidirectional parallel version of

this study, to see what insights this may yield in addition to what we

have now learnt from the comparable part of the study.

6. Bidirectional Version of the Study

The first step in this part of the analysis is to give an overview of the

number of occurrences of the English and Norwegian patterns in the

original texts and to what degree they correspond to each other in

translation. In other words, we are concerned with congruent and non-

congruent correspondences of the patterns, where congruent means

formally similar and non-congruent formally dissimilar (Johansson 2007;

Ebeling & Ebeling 2013a). Table 3 offers a simplified overview of such

correspondences of the patterns in the bidirectional parallel material.

Table 3. Translations of for * sake and for * skyld in the ENPC+ (raw

numbers)

Correspondence

EO > NT

NO > ET

Congruent for * sake = for * skyld

27

18

Non-congruent for * sake/skyld = ‘other’

58

46

Total

85

64

Not surprisingly, based on what has already been shown, the

correspondence in translation between the two patterns is far from 100%.

Going from English into Norwegian (EO > NT): for *sake is translated

congruently into for * skyld in 27 out of the 85 cases, and from

Norwegian into English (NO > ET) in 18 out of 64. Following Altenberg

(1999), this gives a mutual correspondence of only around 30% for the

patterns, i.e. they are only used to translate each other in about 30% of

the cases. Although it is rare to find items with a mutual correspondence

of 100%, such a low cross-linguistic correspondence rate as the one

established for for *sake and for * skyld suggests that the two patterns

have very different conditions of use in their respective languages, thus

Contrastive Analysis, Tertium Comparationis, Corpora

109

adding strength to the conclusions arrived at in the comparable analysis

in Section 5.

The low mutual correspondence begs the question of what actually

happens in the translation of the patterns, not least in the non-congruent

cases. Examples (10)–(12) show the main tendencies for the English

pattern.

English expletive → non-congruent

(10) “They’re just traffic cones, for fuck’s sake.” (PeRo2E)

“Det er jo bare trafikkjegler, for faen.” (PeRo2TN)

Lit.: … for the devil

English consideration → congruent

(11) For my sake. (JB1)

For min skyld. (JB1T)

English purpose → congruent

(12) We stayed together for appearances’ sake … (PeRo2E)

Vi holdt sammen for syns skyld … (PeRo2TN)

Typically, then, the main use in English—the expletive use—is

translated by a non-congruent correspondence in Norwegian, in 54 out of

the 65 cases (see Table 2), as in (10), possibly because this is the least

favoured use of the Norwegian pattern. Both the consideration use in

(11) and the purpose use in (12) represent more natural and idiomatic

uses in Norwegian, and the few cases, are rendered congruently, in 13

out of 17 cases for the consideration use and in three out of three cases

for the purpose use (see Table 2).

Similarly, in the other direction of translation—from Norwegian into

English—the few instances of the expletive use in Norwegian typically

get a congruent expletive translation in English (four out of five), as in

(13). This is also the case for the consideration use in (14), in eight out of

12 cases, whereas the favoured use in Norwegian, purpose, typically gets

a non-congruent correspondence in English (in 41 out of 47 cases; see

Table 2), as shown in (15).

Signe Oksefjell Ebeling and Jarle Ebeling

110

Norwegian expletive → congruent

(13) - Slipp han nå for guds skyld ned. (PePe1N)

“Put him down, for God’s sake.” (PePe1TE)

Norwegian consideration → congruent

(14) … hun gjorde det for pappas skyld … (PeRy1N)

… she was doing it for Dad’s sake … (PeRy1TE)

Norwegian purpose → non-congruent

(15) Han rygget et skritt for sikkerhets skyld. (KaFo1N)

Lit.: … for safety’s sake

He retreated a step, just to be on the safe side. (KaFo1TE)

The tendencies reported in both directions of translation corroborate, and

add more confidence to, the findings from the comparable (part of the)

study with regard to preferred meanings and uses: expletive in English

and purpose in Norwegian. In addition, the bidirectional study provides

non-congruent correspondences in both directions of translation showing

by which means (forms) the expletive use is rendered in Norwegian and

the purpose use in English. Thus, a more robust contrastive analysis is

achieved.

In the following, we will look in more detail at the non-congruent

correspondences of the two uses that differ the most. We start with the

purpose use in Norwegian before moving on the the expletive use in

English in order to see how these uses are expressed in the other

language in terms of non-congruent correspondences, both as translations

and as sources.

The most frequent purpose expressions in the Norwegian data are for

sikkerhets skyld ‘for safety’s sake’ and for moro skyld ‘for fun sake’, and

Table 4 shows the two correspondence patterns that are clearly preferred

to express the former of these in English (to be on the safe side and just

in case). Another pattern is clearly preferred to express the latter, namely

for + Noun, as in for fun, for pleasure etc.). The ‘other’ expressions

referred to in Table 4 are not tied to specific nouns in the open slot in

Norwegian, but quite a few of the English correspondences have the

fixed expressions a matter of and for the sake of followed by a noun.

Contrastive Analysis, Tertium Comparationis, Corpora

111

Table 4. The most salient non-congruent English correspondences

(translations and sources) of the most frequent Norwegian purpose uses

with for * skyld

for sikkerhets skyld (‘for

safety’s sake’)

for moro skyld (‘for fun’s

sake’)

Other

to be on the safe side

just in case

for N (fun / entertainment

/ pleasure)

a matter of N

for the sake of N

As for the English expletive use, the three most frequent sequences in the

English texts are for Christ’s sake, for fuck’s sake and for God’s sake.

The most salient non-congruent Norwegian correspondences are listed in

Table 5.

Table 5. The most salient non-congruent Norwegian correspondences

(translations and sources) of the most frequent English expletives with for

* sake

for Christ’s sake

for fuck’s sake

for God’s sake

for svingende (lit. ‘for

swinging’)

for svingende (lit. ‘for

swinging’)

herregud (‘God’, lit.

‘lordgod’)

herregud (‘God’, lit.

‘lordgod’)

helvete (‘hell’)

(for) faen (‘(for) the

devil’)

(for) faen (‘(for) the

devil’)

i herrens navn (‘in the

lord’s name’)

It is interesting to note that there is some overlap in the Norwegian

correspondences of the three different English expletive patterns. Both

for Christ’s sake and for God’s sake have herregud ‘lordgod’ and the

rather strange expression for svingende ‘for swinging’. While the former

is an expletive within the same domain as Christ and God, for svingende

can, as pointed out in Ebeling & Ebeling (2014: 203), be considered a

pretend or quasi-swear word or nestenbanning (‘almost-swearing’) in

Hasund’s (2005) terms. For svingende is only found in the translations,

and it could be argued that the translators have tried to tone down the

Signe Oksefjell Ebeling and Jarle Ebeling

112

expletive, even if for Christ’s sake and for God’s sake are thought of as

fairly mild expletives.

The other overlap in the correspondences is arguably more curious,

as the two English expletives—one from the sexual domain (for fuck’s

sake) and one from the celestial (for God’s sake)—both are found to

correspond to the diabolical faen ‘the devil’. This is in fact the most

common Norwegian correspondence of the English expletive overall.

Of the two remaining, relatively common non-congruent

correspondences shown in Table 4, i herrens navn ‘in the lord’s name’

seems a more natural and unmarked correspondence of for God’s sake

than helvete ‘hell’ is of for Christ’s sake.

Although we can merely speculate at this stage, observations like

these may tell us something about a culture’s swearing preferences, with

English being, in this pattern at least, drawn towards the celestial and

sexual, while Norwegian is drawn either towards the diabolical or the

celestial (herregud, i herrens navn).

6.1 Summary of the Bidirectional Parallel Study

In addition to uncovering different preferences of use in English and

Norwegian (including different extended-units-of-meaning) on the basis

of both comparable and parallel data, we have been able to demonstrate

that access to, and analysis of, bidirectional translation data means that

we, through translation as TC, can offer corresponding, and arguably

more equivalent, expressions of the for * sake / for * skyld pattern in the

other language. For example, typical Norwegian expletives

corresponding to the expletive for * sake pattern emerged, and similarly,

other and more typical English expressions of purpose corresponding to

the purpose for * skyld pattern emerged. These can be further explored in

a more comprehensive contrastive study of swearing and the expression

of purpose between the two languages. In addition, highlighting the

importance of bidirectionality, the “soft” Norwegian correspondence of

the English expletive (for svingende) may be considered less equivalent

than the other correspondences since it was only attested in the translated

material. Moreover, the observation from the comparable study that the

patterns seem to be cross-linguistically most similar to each other in the

consideration use was not only confirmed on the basis of the

Contrastive Analysis, Tertium Comparationis, Corpora

113

bidirectional data, but further evidence was brought to the table through

the large proportion of congruent correspondences.

We believe that we gain a deeper understanding of the items

compared when using a bidirectional parallel technique as it offers a

more comprehensive contrastive account of the patterns compared. It

should also be mentioned that a bidirectional parallel study like this one

could, and perhaps even should, serve as a starting point for further

investigations that draw on much larger comparable monolingual

corpora.

7. Concluding Remarks

In this article we have outlined some of the main types of corpora used in

contrastive research and pointed out some of their strengths and

weaknesses. In general terms, these can be summarized as follows: To

investigate cross-linguistic correspondence and equivalence on the basis

of a comparable corpus, researchers typically take predefined items or

categories as their starting point, emerging from a perceived similarity

(or even dissimilarity in some cases) in two or more languages (e.g.

causative constructions). The CA in these cases may be based on the

researcher’s bilingual knowledge, dictionaries, grammars, and earlier

research of previously identified causative constructions.

Parallel bidirectional corpora, on the other hand, add the dimension

of having access to a pool of translators’ bilingual competence, and what

choices the translators make in similar linguistic situations. This enables

investigations of both predefined and undefined items through perceived

similarities or dissimilarities. Moreover, there is arguably more room for

purely exploratory studies when the contrastive analysis is based on

bidirectional translation data.

Following these general observations regarding different types of

corpora and the tertia comparationis they represent, an attempt was

made to directly compare the two different copus-based contrastive

methods by performing two versions of the “same” cross-linguistic

study. The rationale behind this exercise was to see to what extent it

would lend support to the view held by some contrastive linguists that

correspondence in translation is a good tertium comparationis if applied

to carefully structured bidirectional parallel corpora. It was found that a

bidirectional study arguably yielded more robust cross-linguistic results

Signe Oksefjell Ebeling and Jarle Ebeling

114

as it has the extra advantage of providing translation paradigms. The

bidirectionality of such corpora also ensures that the researcher can

control for translation effects, i.e. potential translation-specific features.

It should be stressed that the idea of using bidirectional data for

contrastive analysis is not our own. We are indebted to Stig Johansson, in

particular, for devising a corpus integrating comparable monolingual and

bilingual translation data within the same model, as first seen in the

English-Norwegian Parallel Corpus (ENPC) (Johansson & Hofland

1994). The structure of the ENPC clearly yields results that are arguably

superior to results obtained exclusively on the basis of comparable

data—at least if the aim is to gain insight into the full cross-linguistic

picture. As pointed out by Aijmer (2008: 208),

[i]t is difficult to see how any other method could give such a clear and detailed

picture of the relationship between the languages and contribute to the language-

specific description of the languages compared.

However, comparable corpora are indispensable in contrastive studies,

particularly when integrated within a bidirectional parallel set-up, but

also as providers of more extensive data sets. Indeed, in a recent

publication by Granger (2018: 183), a methodological framework termed

Contrastive Translation Analysis is introduced, where a “multi-corpus

empirical basis for corpus-based crosslinguistic studies” is called for. In

this framework, both comparable and parallel corpora have a place and,

in addition, learner corpora of the languages being compared (ibid. 190).

References

Aijmer, Karin. 2008. “Parallel corpora and comparable corpora.” Corpus

Linguistics. An International Handbook, Vol. 1. Eds. Anke Lüdeling

and Merja Kytö. Berlin / New York: Walter de Gruyter. 275–292.

Aijmer, Karin, Bengt Altenberg and Mats Johansson (eds). 1996.

Languages in Contrast. Papers from a Symposium on Text-based

Cross-linguistic Studies. Lund 4–5 March 1994. Lund: Lund

University Press.

Altenberg, Bengt. 1982. The Genitive v. the of-construction: A Study of

Syntactic Variation in 17th Century English. Lund: Gleerup.

Altenberg, Bengt. 1999. “Adverbial connectors in English and Swedish:

Semantic and lexical correspondences.” Out of Corpora. Studies in

Contrastive Analysis, Tertium Comparationis, Corpora

115

Honour of Stig Johansson, Eds. Hilde Hasselgård and Signe

Oksefjell. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 249–268.

Altenberg, Bengt and Sylviane Granger. 2002. “Recent trends in cross-

linguistic lexical studies.” Lexis in Contrast. Corpus-based

Approaches. Eds. Bengt Altenberg and Sylviane Granger.

Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 3–48.

Biber, Douglas. 1995. Dimensions of Register Variation. Cambridge:

CUP.

Chesterman, Andrew. 1998. Contrastive Functional Analysis.

Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Dyvik, Helge. 1998. “A translational basis for semantics.” Corpora and

Cross-linguistic Research: Theory, Method, and Case Studies. Eds.

Stig Johansson and Signe Oksefjell. Amsterdam/Atlanta: Rodopi.

51–86.

Ebeling, Jarle and Signe Oksefjell Ebeling. 2013a. Patterns in Contrast.

Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Ebeling, Signe Oksefjell and Jarle Ebeling. 2013b. “From Babylon to

Bergen: On the usefulness of aligned texts.” Bergen Language and

Linguistics Studies (BeLLS) 3(1), 23–42.

Ebeling, Signe Oksefjell and Jarle Ebeling. 2014. “For Pete’s sake! A

corpus-based contrastive study of the English/Norwegian patterns

‘for * sake’/ ‘for * skyld’.” Languages in Contrast 14(2), 191–213.

Frawley, William. 1984. Translation. Literary, Linguistic &

Philosophical Perspectives. Newark: University of Delaware Press.

Gellerstam, Martin. 1986. “Translationese in Swedish novels translated

from English.” Translation Studies in Scandinavia. Eds. Lars Wollin

and Hans Lindquist. Lund: CWK Gleerup. 88–95.

Granger, Sylviane. 2018. “Tracking the third code. A cross-linguistic

corpus-driven approach to metadiscursive markers.” The Corpus

Linguistics Discourse. In Honour of Wolfgang Teubert. Eds. Anna

Čermáková and Michaela Mahlberg. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

185–204.

Hasselgård, Hilde. 2010. “Contrastive analysis/contrastive linguistics.”

The Routledge Linguistics Encyclopedia. Ed. Kirsten Malmkjær.

London: Routledge. 98–101.

Hasselgård, Hilde. Forthc. “Corpus-based contrastive studies:

beginnings, developments and directions.” To appear in Languages

in Contrast 2020:2.

Signe Oksefjell Ebeling and Jarle Ebeling

116

Hasund, Ingrid Kristine. 2005. Fy Farao! Om nestenbanning og andre

kraftuttrykk. Oslo: Cappelen.

James, Carl. 1980. Contrastive Analysis. London: Longman.

Johansson, Stig. 2001. “The English verb seem and its correspondences

in Norwegian: What seems to be the problem?” A Wealth of English.

Studies in Honour of Göran Kjellmer, Ed. Karin Aijmer. Göteborg:

Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis. 221–245.

Johansson, Stig. 2007. Seeing through Multilingual Corpora: On the Use

of Corpora in Contrastive Studies. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Johansson, Stig. 2011. “A multilingual outlook of corpora studies.”

Perspectives on Corpus Linguistics. Eds. Viana Vander, Sonia

Zyngier and Geoff Barnbrook. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 115–

129.

Johansson, Stig. 2012. “Cross-linguistic perspectives.” English Corpus

Linguistics: Crossing Paths. Ed. Merja Kytö. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

45–68.

Johansson, Stig and Knut Hofland. 1994. “Towards an English-

Norwegian parallel corpus.” Creating and Using English Language

Corpora: Papers from the Fourteenth International Conference on

English Language Research on Computerized Corpora, Zurich 1993,

Eds. Udo Fries, Gunnel Tottie and Peter Schneider. Amsterdam:

Rodopi. 25–37.

Lexico.com. 2019. Powered by OUP.

Mair, Christian. 2018. “Contrastive analysis in linguistics.” Oxford

Bibliographies Online, https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/. DOI:

10.1093/obo/9780199772810-0214.

McEnery, Tony and Richard Xiao. 2007. “Parallel and comparable

corpora: What is happening?” Incorporating Corpora. The Linguist

and the Translator. Eds. Gunilla M. Anderman and Margaret Rogers.

Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. 18–31.

Oxford English Dictionary (OED) Online. 2020. Oxford: OUP.

http://oed.com/.

Sinclair, John. 1996. “The search for units of meaning.” Textus IX: 75–

106.

Teich, Elke. 2003. Cross-Linguistic Variation in System and Text. A

Methodology for the Investigation of Translation and Comparable

Texts. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Contrastive Analysis, Tertium Comparationis, Corpora

117

Teubert, Wolfgang. 1996. “Comparable or parallel corpora?”

International Journal of Lexicography, 9(3), 238–264.

Volansky, Vered, Noam Ordan and Shuly Wintner. 2013 [online pub.].

“On the features of translationese.” Literary and Linguistic

Computing 30(1) 2015, 98–118. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/

llc/fqt03